PC&P (Pictures, Culture & Politics) P & C (Papers & Coffee) PP&P (Pub, Pint & Peanuts)

Friday, April 30, 2010

iPhone Drama - California Style

Twenty-one-year-old Redwood City, California, resident Brian J. Hogan, the man identified by Wired.com as the guy who found — and later sold — Apple's missing iPhone in a bar last month, has a message for Apple, the engineer who originally lost the precious gadget, and the tech world at large: Sorry about that.

Following a trail of "clues" on social-networking sites and confirming his ID with a source "involved in the iPhone find," Wired named Hogan on Thursday as the bar patron who made off with Apple's top-secret iPhone prototype and then sold it to Gizmodo for $5,000 after an Apple software engineer left the precious phone on a bar stool.Up until now, Hogan's identity has been a mystery to the public, but the 21-year-old college student (or at least, he was a college student as of 2008) may have sensed that he was in trouble after all the hoopla over Gizmodo's gigantic iPhone scoop last week and the subsequent fallout, including a raid on Gizmodo editor Jason Chen's house by San Mateo sheriff's deputies armed with a search warrant.

Hogan has now lawyered up, and in a statement released through his attorney, the young man says he "regrets his mistake in not doing more to return the phone," and that he thought his $5,000 deal with Gizmodo was only "so that they could review the phone," Wired reports.

According to Hogan's attorney's statement, Hogan didn't see the lost iPhone until another patron at the Redwood City bar came up and asked him if it was his; Hogan apparently then asked a few other patrons if they'd lost the device before heading out, iPhone in hand, according to Wired.

Initial reports had it that the man who'd taken the iPhone tried repeatedly to call the Apple Care support line to return the phone, but according to the statement in the Wired story, Hogan never personally called Apple, although a friend of his offered to. The owners of the bar where the iPhone was lost also told Wired that Hogan never bothered to call them about the lost hardware, although the anguished Apple engineer who mislaid the iPhone "returned several times" to see if it had turned up.

Meanwhile, CNET is reporting that Hogan had help in finding a buyer for the lost iPhone. The "go-between," according to CNET: 27-year-old Sage Robert Wallower, a UC Berkeley student who "contacted technology sites" about the handset. Wallower told CNET that he "didn't see it or touch it in any manner" but knows "who found it," adding, "I need to speak to a lawyer ... I think I have said too much."

No one has been charged yet in the case of the lost iPhone, but a deputy district attorney for San Mateo County tells Wired that Hogan is "very definitely ... being looked at as a suspect in theft." (In California, finding a piece of lost property isn't a case of "finders keepers"; if you find a lost item and keep it without making "reasonable" efforts to find the real owner, you could be charged with a crime.)

Gizmodo's Jason Chen also has yet to be charged; law-enforcement officials have reportedly said they'll hold off on searching the computers and servers seized from Chen's house until they decide whether California's shield law for journalists applies to him.

Thursday, April 29, 2010

A Greek Dra(ch)ma

Why is Greece still in crisis, wasn't there a bailout?

After months of uncertainty, the EU and IMF had finally offered a €45bn rescue package (€30bn from Europe and €15bn from the IMF), which might have seen Greece through its short-term borrowing needs. But political opposition in Germany led investors to lose confidence and drove up Greek borrowing costs to the point where a far bigger rescue package now looks necessary.

What happens if a bigger bailout can't be agreed?

With short-term borrowing rates hitting 38% on Wednesday, investors fear Greece will have no choice but to default on some of its existing debt obligations, or at the very least negotiate a partial debt restructuring. In short, refuse to pay. The latest crisis was sparked on Tuesday when credit rating agency Standard & Poors downgraded Greek sovereign bonds to junk status.

Why is this so bad? Don't the bankers deserve it?

It is bad for Greece because it will make it almost impossible to borrow its way out of trouble in future, making it difficult to pay all its public sector employees and deepening its recession. It is bad for everyone because most fund managers invest in these bonds on behalf of international pensioners and savers. Though Goldman Sachs has been criticised for helping Greece hide its problems and hedge funds are blamed for exacerbating the market reaction, the banking industry is far less culpable in this crisis than it was last year.

Will Greece leave the euro?

If its domestic economic crisis gets bad enough, Athens may decide a currency devaluation is the only way to restore international competitiveness. It is hard to imagine it would restore the drachma with so many corporate and household debts still denominated in euros.

How might the contagion spread?

Rating agencies have downgraded government debt issued by Spain and Portugal, suggesting greater fears of default and higher borrowing costs across much of southern Europe. The cost of insuring against default in Poland and Ireland has also jumped as the so-called "sovereign" credit market suffers a widespread loss of confidence. Confidence could quickly return if European governments agree a more convincing rescue plan when they meet on 10 May.

Could the UK be next?

A wider collapse in investor confidence could make it more expensive for the UK to continue its heavy borrowing programme too. Lying outside the single currency means this would probably express itself first in a sharp fall in sterling rather than an outright "gilts strike" (when investors refuse to buy UK government bonds). Interest rates would also have to rise, potentially pushing the economy back into recession.

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

Via Crucis

You cross it every day, by bike, in your way to work.

A big crossroad is not, neither a special one.

It´s small, humble, an ordinary one.

That´s why you were struck when you saw that Police notice:

“Fatal accident, if you have witnessed something please contact us”.

Since then

Week in- week out

You see fresh flowers

Attached to the lamppost

In the middle of the crossroad.

Someone even wrote a poem

Mourning the dead son.

Months passed by and today

You rode by there again.

There is the bunch of fresh flowers

There the hurting poem, wrapped in cello tape

So the rain doesn´t corrupt

An incorruptible feeling.

Every time you see it

It gives you goosebumps

Someone really did lose

Someone important

A certain number in the calendar

Brings sour memories to someone

A cyclic pain

The need of placing flowers

Flowers that will ease the pain

At least a bit

An I Love You to the gone one

A You Are With Me

An I Don´t Forget You.

Monday, April 26, 2010

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Sunday, April 18, 2010

Roland Garros

Roland Garros (October 6, 1888 – October 5, 1918) was an early French aviator and a fighter aircraft pilot during World War I.

Biography

Garros was born in Saint-Denis, Réunion. He started his aviation career in 1909 flying Santos-Dumont's Demoiselle monoplane, an aircraft that only flew well with a small lightweight pilot. In 1911 Garros graduated to flying Bleriot monoplanes and entered a number of European air races with this type of machine. He was already a noted aviator before World War I; by 1913 he had switched to flying Morane-Saulnier monoplanes, a vast improvement over the Bleriot, and gained fame for making the first nonstop flight across the Mediterranean Sea from Fréjus in south of France to Bizerte in Tunisia.

The following year, Garros joined the French army at the outbreak of the conflict. After several aerial missions he decided that shooting and flying at the same time was too difficult, so he fitted a machine gun to the front of his plane so the tasks became one and the same. In order to protect the propeller from the bullets, he fitted metal wedges to the prop. Starting from April 1, 1915, he soon shot down three German planes and quickly gained an excellent reputation.

On April 18, 1915, his fuel line clogged and he glided to a landing on the German side of the lines. After examining Garros's plane, German aircraft engineers designed an improved system known as the interrupter gear. Soon the tables were reversed against the Allies due to Fokker's planes shooting down nearly every enemy aircraft they met, leading to what became known as the Fokker Scourge.

Garros managed to escape from a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany in February 1918 and rejoined the French army. On October 5, 1918, he was shot down and killed near Vouziers, Ardennes, a month shy of the end of the war.

Garros is erroneously called the world's first fighter ace. In fact, he shot down three aircraft, and the honor of the first ace went to another French airman, Adolphe Pegoud.

Places named after Roland Garros

In the 1920s, a tennis centre was named after the pilot, Stade de Roland Garros. The stadium accommodates the French Open, one of tennis' Grand Slam tournaments. Consequently, the tournament is officially called Roland Garros.

The international airport of La Réunion, Roland Garros Airport, is also named after him.

Peugeot Car Manufacturers (French) commissioned a 'Roland Garros' limited edition version of its 205 model in celebration of the Tennis Tournament that bears his name. The model included special paint and leather interior. Due to the success of this special edition, Peugeot later created Roland Garros editions of its 106, 206, 306 and 806 models.

Saturday, April 17, 2010

Poem Of The Day

BEFORE WE GET INTO THIS

Before we get to know each other

And sing for tomorrow

And unearth yesterday

So that we can prepare our joint grave

You should know that I have no family,

Neither disowned nor distanced - none.

No birthdays nor Christmas,

No telephone calls. It's been that way

Since birth for what it's worth

No next of skin.

I am the guilty secret of an innocent woman

And a dead man - tell your parents, they'll want to know.

by Lemn Sissay

Friday, April 16, 2010

Single Black Women

IMAGINE that the world consists of 20 men and 20 women, all of them heterosexual and in search of a mate. Since the numbers are even, everyone can find a partner. But what happens if you take away one man? You might not think this would make much difference. You would be wrong, argues Tim Harford, a British economist, in a book called “The Logic of Life”. With 20 women pursuing 19 men, one woman faces the prospect of spinsterhood. So she ups her game. Perhaps she dresses more seductively. Perhaps she makes an extra effort to be obliging. Somehow or other, she “steals” a man from one of her fellow women. That newly single woman then ups her game, too, to steal a man from someone else. A chain reaction ensues. Before long, every woman has to try harder, and every man can relax a little.

Real life is more complicated, of course, but this simple model illustrates an important truth. In the marriage market, numbers matter. And among African-Americans, the disparity is much worse than in Mr Harford’s imaginary example. Between the ages of 20 and 29, one black man in nine is behind bars. For black women of the same age, the figure is about one in 150. For obvious reasons, convicts are excluded from the dating pool. And many women also steer clear of ex-cons, which makes a big difference when one young black man in three can expect to be locked up at some point.

Removing so many men from the marriage market has profound consequences. As incarceration rates exploded between 1970 and 2007, the proportion of US-born black women aged 30-44 who were married plunged from 62% to 33%. Why this happened is complex and furiously debated. The era of mass imprisonment began as traditional mores were already crumbling, following the sexual revolution of the 1960s and the invention of the contraceptive pill. It also coincided with greater opportunities for women in the workplace. These factors must surely have had something to do with the decline of marriage.

But jail is a big part of the problem, argue Kerwin Kofi Charles, now at the University of Chicago, and Ming Ching Luoh of National Taiwan University. They divided America up into geographical and racial “marriage markets”, to take account of the fact that most people marry someone of the same race who lives relatively close to them. Then, after crunching the census numbers, they found that a one percentage point increase in the male incarceration rate was associated with a 2.4-point reduction in the proportion of women who ever marry. Could it be, however, that mass incarceration is a symptom of increasing social dysfunction, and that it was this social dysfunction that caused marriage to wither? Probably not. For similar crimes, America imposes much harsher penalties than other rich countries. Mr Charles and Mr Luoh controlled for crime rates, as a proxy for social dysfunction, and found that it made no difference to their results. They concluded that “higher male imprisonment has lowered the likelihood that women marry…and caused a shift in the gains from marriage away from women and towards men.”

Similar problems afflict working-class whites, but they are more concentrated among blacks. Some 70% of black babies are born out of wedlock. The collapse of the traditional family has made black Americans far poorer and lonelier than they would otherwise have been. The least-educated black women suffer the most. In 2007 only 11% of US-born black women aged 30-44 without a high school diploma had a working spouse, according to the Pew Research Centre. Their college-educated sisters fare better, but are still affected by the sex imbalance. Because most seek husbands of the same race—96% of married black women are married to black men—they are ultimately fishing in the same pool.

Black women tend to stay in school longer than black men. Looking only at the non-incarcerated population, black women are 40% more likely to go to college. They are also more likely than white women to seek work. One reason why so many black women strive so hard is because they do not expect to split the household bills with a male provider. And the educational disparity creates its own tensions. If you are a college-educated black woman with a good job and you wish to marry a black man who is your socioeconomic equal, the odds are not good.

“I thought I was a catch,” sighs an attractive black female doctor at a hospital in Washington, DC. Black men with good jobs know they are “a hot commodity”, she observes. When there are six women chasing one man, “It’s like, what are you going to do extra, to get his attention?” Some women offer sex on the first date, she says, which makes life harder for those who prefer to combine romance with commitment. She complains about a recent boyfriend, an electrician whom she had been dating for about six months, whose phone started ringing late at night. It turned out to be his other girlfriend. Pressed, he said he didn’t realise the relationship was meant to be exclusive.

The skewed sex ratio “puts black women in an awful spot,” says Audrey Chapman, a relationship counsellor and the author of several books with titles such as “Getting Good Loving”. Her advice to single black women is pragmatic: love yourself, communicate better and so on. She says that many black men and women, having been brought up by single mothers, are unsure what role a man should play in the home. The women expect to be in charge; the men sometimes resent this. Nisa Muhammad of the Wedded Bliss Foundation, a pro-marriage group, urges her college-educated sisters to consider marrying honourable blue-collar workers, such as the postman. But the simplest way to help the black family would be to lock up fewer black men for non-violent offenses.

Ash Thursday

Just over 200 years ago an Icelandic volcano erupted with catastrophic consequences for weather, agriculture and transport across the northern hemisphere – and helped trigger the French revolution.

The Laki volcanic fissure in southern Iceland erupted over an eight-month period from 8 June 1783 to February 1784, spewing lava and poisonous gases that devastated the island's agriculture, killing much of the livestock. It is estimated that perhaps a quarter of Iceland's population died through the ensuing famine.

Then, as now, there were more wide-ranging impacts. In Norway, the Netherlands, the British Isles, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, in North America and even Egypt, the Laki eruption had its consequences, as the haze of dust and sulphur particles thrown up by the volcano was carried over much of the northern hemisphere.

Ships moored up in many ports, effectively fogbound. Crops were affected as the fall-out from the continuing eruption coincided with an abnormally hot summer. A clergyman, the Rev Sir John Cullum, wrote to the Royal Society that barley crops "became brown and withered … as did the leaves of the oats; the rye had the appearance of being mildewed".

The British naturalist Gilbert White described that summer in his classic Natural History of Selborne as "an amazing and portentous one … the peculiar haze, or smokey fog, that prevailed for many weeks in this island, and in every part of Europe, and even beyond its limits, was a most extraordinary appearance, unlike anything known within the memory of man.

"The sun, at noon, looked as blank as a clouded moon, and shed a rust-coloured ferruginous light on the ground, and floors of rooms; but was particularly lurid and blood-coloured at rising and setting. At the same time the heat was so intense that butchers' meat could hardly be eaten on the day after it was killed; and the flies swarmed so in the lanes and hedges that they rendered the horses half frantic … the country people began to look with a superstitious awe, at the red, louring aspect of the sun."

Across the Atlantic, Benjamin Franklin wrote of "a constant fog over all Europe, and a great part of North America".

The disruption to weather patterns meant the ensuing winter was unusually harsh, with consequent spring flooding claiming more lives. In America the Mississippi reportedly froze at New Orleans.

The eruption is now thought to have disrupted the Asian monsoon cycle, prompting famine in Egypt. Environmental historians have also pointed to the disruption caused to the economies of northern Europe, where food poverty was a major factor in the build-up to the French revolution of 1789.

Volcanologists at the Open University's department of earth sciences say the impact of the Laki eruptions had profound consequences.

Dr John Murray said: "Volcanic eruptions can have significant effects on weather patterns for from two to four years, which in turn have social and economic consequences. We shouldn't discount their possible political impacts."Thursday, April 15, 2010

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

Sunday, April 11, 2010

Not so in touch

The iPad

(OK, it's not a person. But at least it has nothing to do with the election, so – onward.) It still has no camera; no USB port; no replaceable battery; too shiny a screen; too slippery a texture; no obvious advantage over a laptop, an iPhone; it doesn't support Flash; you still can't download apps accept from Apple; it costs $499 (£325) and sold 300,000 within hours of going on sale in the US. It took about 37½ seconds for the first complaints to come in. Hundreds of users reported difficulties connecting to Wi-Fi and are waiting to hear if this is owing to a software problem (easy-peasy fix) or hardware flaw (to the Apple store and fling-device-through-window fix). Those of us content to stay a safe distance from the bleeding edge of technology settle back and tell them we'll be along when they've got everything sorted out. Ta.

by Lucy Mangan

Saturday, April 10, 2010

Newstralia?

New Zealand is talking about whether to become part of Australia. It would be a sad step for a country which has used its independence to set an example for the rest of the world, says Simon Schama.

On a recent Sunday morning in New Zealand I'm waiting to do a turn on breakfast TV with a tough, veteran presenter, Paul Holmes, whose sharp tailoring at an hour when most of us are still in pyjamas seems, all by itself, a reproach to dozy thinking.

I'm in a studio in Wellington; he's in Auckland. We are connected by a satellite feed, but there is something about Paul that reminds me of a Latin teacher who had an uncanny knack for spotting where my mind was wandering. The rest of the class would be plodding through Parthia with Caesar's legions, but Schama? He was off somewhere on a Pacific lagoon backing up Elvis as grass skirts swayed to a tropic breeze.

"Boy at the back WAKE UP!" the Master Conjugator would roar and you can bet I did. So, this Sunday, even though my fellow writers at the Wellington festival have been making friends with the Pinot Noir until all hours, I sit up straight in the studio and pay attention as Paul and his politician guests tackle a painful question for the half-hour before my interview.

That subject turns out to be the suicide of New Zealand. No not suicide in New Zealand but a proposal to cash in the country's independence and become instead, the seventh state of the Australian commonwealth. An opinion poll has suggested that no less than one in four New Zealanders are in favour of this startling departure, and fully a half of the polled want to begin serious debate about it.

What - in the name of Edmund Hillary, the haka and all things Kiri te Kanawa - are they talking about? Don't they know that Poms live for the moments - and they happen all too infrequently - when the Aussies get shafted by the Men in Black?

Isn't it bad enough they have the sunshine, the terminally cute wombat, and Nicole Kidman? Must they get the kiwi and the juiciest spring lamb in the world too?

The reasons habitually given for this overture are, surprise, surprise economic and not without a steely logic. Over the past two decades, per capita incomes in the two countries on opposite sides of the Tasman Sea have been diverging with New Zealand on the short end of the trend.

Young brains have been draining to Melbourne, Sydney and Perth. As the British and Irish descendants depart for Oz, the great trans-Pacific Asian migration moves in.

New Zealand is one of the least racially defensive places on the face of the Earth, but even in high-minded circles there's anxiety about a shift in cultural identity. Which seems to me to be even less of a reason to cash in that identity in for the Mephistophelian allure of the mineral-rich economy of Australia.

I must have registered shock for when Paul asks me to chip in, the words "birthright" and "mess of pottage" escape my lips.

Some days later in Sydney, though, I can see the point of kiwis who are thinking the unthinkable. Is there any more gorgeous city on the face of the Earth? No, there isn't.

Paris? Oh please: food and fashion are so over. New York? Uninspired modern art and punitive traffic on the West Side Highway. London. OK the great world city. But unlike London, the economic outlook in Sydney is as sunny as the weather.

Future of megastates

Unemployment stands at 5%. Property prices are going up. As are glittering high rise office towers, designed by the usual premier league of celebrity architects. The creamily clad Opera House sits enthroned on its pedestal in the harbour, as the muscle-toned and the tanned jog by the water.

And for a moment you say to yourself, well, all right, who wouldn't want to be along for that kind of thrilling Aussie ride into the Pacific-Asian future?

But then you snap out of it. Because you realise that the economic rationale for making New Zealand more Australian is just that - a rationalisation. Something deeper and sadder is lurking here: the embarrassment of smallness.

I take a straw poll in the studio in Wellington and it's only the producer who says yes she'd vote for a union tomorrow because the country might stake more of a claim in the coming world. By which she means the world of the economic megastates whose population is counted in the hundreds of millions rather than New Zealand's 4.3.

Better to be a tickbird on the hide of the pachyderm than trampled ignominiously beneath its thundering feet is it?

Wretched cookie cutters

To my appeal to leave New Zealand just as it is, my hosts are too polite to retort "that's rich coming from you" and remind me that in 1973 we ran off to the EU; responding to sleeve tugging from the orphaned antipodes with a brush-off telegram: "Thanks a ton for Gallipoli and all the butter, but this is just the way it is. Sorry about the surplus to requirement sheep. Have a nice life."

But even acknowledging the hypocrisy, I still don't want to see New Zealanders selling short the rich history of their peculiar place in the world. I'm not an enthusiast for one-size-fits-all versions of national community: interchangeable airports, cookie-cutter multiplexes, die-stamp shopping malls.

I'm all for micro-anachronism. Long live Andorra! Hail to thee O Liechtenstein! May Sikkim never perish from the face of the Earth.

I own up to a smidgin of nostalgia here. For anyone who grew up in the 1950s, it's a weird and not unpleasant experience to travel thousands of miles to the opposite ends of the Earth and, in New Zealand's smaller towns, arrive where you began your life amidst drizzle-sprayed bowling greens, rose gardens, and shops selling Bassett's Liquorice Allsorts.

But that's the knitted tea-cosy cliche about the country. The strength of its history could not be less purl and plain.

Wherever you look, the New Zealand story has been heroic, volcanic, singular. Its island masses, torn from Gondwanaland, stayed so remote that for millions of years they knew no mammalian life. Insects, reptiles and birds shared the lush ecology and without any predators, many birds evolved flightlessly.

Zoological miracle

In an ambitious ecological restoration project, set around an old 19th Century Wellington reservoir, it's possible to get a glimpse of that miracle of zoological idiosyncrasy. Deep in the shade of tree ferns, a lizard-like tuatara, identical to its ancestors 200 million years ago, snoozes, its skin papery, eyelids wrinkled like some retired professor taking a nap.

Higher up a tui bird goes through its sweetly comical repertoire of impersonations, sounding first like the winding of an old clock, then Susan Boyle in top form.

But the exceptional New Zealand history that needs to be preserved is human. Whatever its ethnic and social battles, New Zealand has often led the way. In 1893 it was the first country in the world to give women the vote, and it was the first to offer old-age pensions to the poor.

But it's the story of Maori and pakeha, the settlers of European origin, that - for all the pain, betrayals and suffering - still deserve to be known and celebrated as offering a different model of cultural encounter than anywhere else in the world.

The 1840 Treaty of Waitangi which, in usual imperial style, seized sovereignty from the Maori and laid it at the feet of Queen Victoria did so on condition that their property rights and political and cultural integrity were respected. Needless to say in the generations that followed, this pact was respected more in the breach than the observance, but New Zealand history did follow its own extraordinary course.

In their first wars against violations of Waitangi the Maori effectively won the battle with the pakeha. Decimated by imported diseases for which they had no immunity, the Maori were expected, at the turn of the 20th Century to be on their way to extinction or extreme marginalisation like native Americans or Australian aborigines. Nothing of the sort has happened.

Today they constitute - by one count - almost 20% of the population and astonishingly a special tribunal created in the 1970s has been ruling on land claims dating back to the post-Waitangi years. Maori and the descendants of intermarriages that go back deep into the 19th Century, are to be found in every leading walk of life in the country.

Of course there have been serious problems of unequal social opportunity, of street gangs. But if there is anywhere in the post-colonial world where two cultural worlds truly live an engaged life alongside each other, it's in New Zealand.

Such stories don't come along very often. Cherish them. Chant them. Dance them.

Upane upane, kaupane, whiti te ra! Up the ladder, up the ladder, the Sun Shines.

Friday, April 09, 2010

Flu Pandemic: Dr WHO or Big Pharma?

It emerged this week that the Department of Health over-bought swine flu jabs by 30 million doses or, to interject coarsely with mention of money, £150m. That money went somewhere: Big Pharma, the target of nineties-noughties conspiracists. In this case, it was GlaxoSmithKline, though there was originally a side order with Smaller Pharma, Baxter.

While the Tories try to make mileage out of an alleged mishandling, Labour MP Paul Flynn questions the advice from the World Health Organisation that spurred the huge purchase in the first place. He points to all the recent scares that have failed to live up to their deadly billing: Sars, CJD, avian flu. Flynn is involved in a Council of Europe inquiry into the influence of drug companies on government policy, so is likely to be trenchant. Still, I was surprised by his boldness when he said, on the Today programme yesterday: "Did they make these terrifying claims because of epidemiology or did they do it under pressure from pharmaceutical companies?"

It's an enormous charge against the WHO. If it were to stand up, the consequences would be vast. The idea of a central, co-ordinated advisory body on health would probably be ended.

The organisation itself, not surprisingly, refutes this in the strongest terms. Gregory Hartl, a WHO spokesman, said: "Unequivocally, there is no influence on the WHO by big pharmaceutical companies. We of course have contact with them. It would be irresponsible of us not to work to develop the best tools possible. At the same time, we do have in place internal safeguards to ensure that vaccine manufacturers or individuals associated with them do not exert influence on WHO." Well, sure, you have to imagine this said with feeling – it does seem a little underpowered.

The British Medical Association is in complete accord. Its pandemic flu chief, Peter Holden, is adamant there were no vested interests anywhere near this – and furthermore puts it in context: the world was due a flu pandemic; the NHS had anticipated the crisis, putting out new guidance for GPs in January 2009; that guidance had to take into account not just the flu itself but the change in national circumstances since the last pandemic, in 1968. We only have two-thirds as many hospital beds as we did in 1997. "There are social changes, both parents in a household probably work, we live in a just-in-time economy, there are only four days' food on the shelves, seven days' supply in pharmacies. We had to keep the hospitals liquid; keep the intensive care system running as long as we could; keep as many people at work as we could. What you want to avoid at all costs is civil disorder." Holden is convinced of, and pretty convincing on, the sagacity of the measures taken. One of his simplest points is that the vaccine was ordered on the understanding that people would need two doses; it turned out one would do, but there was no way of knowing that until it had passed into use.

There's a slight faultline here, which is that H1N1 still turned out to be a disease non-event, and the actions taken by individual countries are only as sensible as the threat level issued by the WHO. Hartl points out that, if you measure it in life years, rather than lives, it has had the largest impact of any flu in recent years – most of its victims being young people, children and pregnant women. "I would use the analogy of a seatbelt; if you wear a seatbelt and don't crash, you don't think that's a waste of time." But there's no cost involved in a seatbelt: we're not yet so grand a species that any cost, however large, is preferable to any risk, however small. "I'm not an economist, I can't get into those kinds of questions."

I don't think the WHO is in the grip of pharmaceutical paymasters: It's enough just being the WHO for most of your threats to be overstated. It is in the nature of epidemiology that it's a blunt tool – all you can do is move with the middle of the graph. So even within the borders of one nation, guidelines won't be right for everybody. You'd expect your own government to be stringent. But there is almost no advice that would work equally well across nearly 200 countries at levels of development that vary from Gabon to Germany.

Very few aspects of health don't rely on factors like population density, sanitation, underlying wellness and access to drugs. So either we have to accept that a centralised body will frequently be pessimistic to the point of purposelessness or we have to let go of the idea of a centralised body altogether. If only there were a conspiracy, this would be a lot easier.

Thursday, April 08, 2010

From My Friend Hillary...

Tomorrow the United States and Russia will sign the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (Start) in Prague, reducing the number of strategic nuclear warheads in our arsenals to levels not seen since the first decade of the nuclear age. This verifiable reduction by the world's two largest nuclear powers reflects our commitment to the basic bargain of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) – all nations have the right to seek the peaceful use of nuclear energy, but they all also have the responsibility to prevent nuclear proliferation, and those that do possess these weapons must work towards disarmament.

This agreement is just one of several concrete steps the United States is taking to make good on President Obama's pledge to make America and the world safer by reducing the threat of nuclear weapons, proliferation and terrorism.

Yesterday the president announced the US government's Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), which provides a roadmap for reducing the role and numbers of our nuclear weapons while more effectively protecting the United States and our allies from today's most pressing threats.

Next week President Obama will host more than 40 leaders at a nuclear security summit for the purpose of securing all vulnerable nuclear materials as swiftly as possible to prevent them from falling into the hands of terrorists.

And along with our international partners, the United States is pursuing diplomatic efforts that create real consequences for states such as Iran and North Korea that defy the global non-proliferation regime.

These steps send clear messages about our priorities and our resolve. To our allies and partners, and all those who have long looked to the United States as an underwriter of regional and global security: our commitment to defend our interests and our allies has never been stronger. These steps will make us all safer and more secure.

To those who refuse to meet their international obligations and seek to intimidate their neighbours: the world is more united than ever before and will not accept your intransigence.

Tomorrow's agreement is a testament to our own determination to meet our obligations under the NPT and the special responsibilities that the United States and Russia bear as the two largest nuclear powers.

The New Start Treaty includes a 30% reduction in the number of strategic nuclear warheads the United States and Russia are permitted to deploy and a strong and effective verification regime, which will further stabilise the relationship between our two countries as well as reduce the risks of miscommunication or miscalculation.

And the treaty places no constraints on our missile defence plans – now or in the future.

President Obama's Nuclear Posture Review makes the principles behind this treaty – and our larger non-proliferation and arms control agenda – part of our national security strategy. Today nuclear proliferation and nuclear terrorism have replaced the cold-war-era danger of a large-scale nuclear attack as the most urgent threat to US and global security. The NPR outlines a new approach that will ensure that our defences and diplomacy are geared towards meeting these challenges effectively.

As part of this new approach, the United States pledges not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear weapons state that is party to the NPT and in compliance with its nuclear non-proliferation obligations. The United States would only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners. There should be no doubt, however, that we will hold fully accountable any state, terrorist group or other non-state actor that supports or enables terrorist efforts to obtain or use weapons of mass destruction.

The NPR also emphasises close co-operation with our allies around the world, and maintains our firm commitment to mutual security. We will work with our partners to reinforce regional security architectures, such as missile defences, and other conventional military capabilities. The United States will continue to maintain a safe, secure and effective nuclear deterrent for ourselves and our allies so long as these weapons exist anywhere in the world.

Nuclear proliferation and terrorism are global challenges, and they demand a global response. That is why President Obama has invited leaders from around the world to Washington for a nuclear security summit and will seek commitments from all nations – especially those that enjoy the benefits of civilian nuclear power – to take steps to stop proliferation and secure vulnerable nuclear materials. If terrorists ever acquired these dangerous materials, the results would be too terrible to imagine.

All nations must recognise that the non-proliferation regime cannot survive if violators are allowed to act with impunity. That is why we are working to build international consensus for steps that will convince Iran's leaders to change course, including new UN security council sanctions that will further clarify their choice of upholding their obligations or facing increasing isolation and painful consequences. With respect to North Korea, we continue to send the message that simply returning to the negotiating table is not enough. Pyongyang must move towards complete and verifiable denuclearisation, through irreversible steps, if it wants a normalised, sanctions-free relationship with the United States.

All these steps, all our treaties, summits and sanctions, share the goal of increasing the security of the United States, our allies, and people everywhere.

Last April President Obama stood in Hradcany Square in Prague and challenged the world to pursue a future free of the nuclear dangers that have loomed over us all for more than a half century. This is the work of a lifetime, if not longer. But today, one year later, we are making real progress towards that goal.

by Hilary Clinton

Wednesday, April 07, 2010

Tuesday, April 06, 2010

Alex in Numberland

When I walked into Pierre Pica's cramped Paris apartment, I was overwhelmed by the stench of mosquito repellent. Pica, a linguist, had just returned from spending five months with a community of Indians in the Amazon rainforest, and he was disinfecting the gifts he had brought back. I asked how the trip had been. "Difficult," he replied.

Alex's Adventures in Numberland

by Alex Bellos

448pp,

Bloomsbury Publishing PLC,

£17.99

For the last 10 years, the focus of Pica's work has been the Munduruku: an indigenous group of about 7,000 people in the Brazilian Amazon whose language has no tenses, no plurals and no words for numbers beyond five. To get to the Munduruku, Pica had to wait for some locals to take him to their territory by canoe.

"How long did you wait?" I inquired.

"I waited quite a lot. But don't ask me how many days."

"So, was it a couple of days?" I suggested tentatively. A few seconds passed as he furrowed his brow: "It was about two weeks."

The more I pushed Pica for facts and figures, the more reluctant he was to provide them. "When I come back from Amazonia, I lose sense of time and sense of number, and perhaps sense of space." This inability to give me quantitative data was part of his culture shock. He had spent so long with people who can barely count that he had lost the ability to describe the world in terms of numbers.

No one knows for certain, but numbers are probably no more than about 10,000 years old. By this, I mean a working system of words and symbols for numbers. One theory is that such a practice emerged together with agriculture and trade, as numbers were an indispensable tool for taking stock and making sure you were not ripped off.

Numbers are so prevalent in our lives that it is hard to imagine how people survive without them. Yet while Pica stayed with the Munduruku, he easily slipped into a numberless existence. He slept in a hammock. He went hunting and ate tapir, armadillo and wild boar. He told the time from the position of the sun. If it rained, he stayed in; if it was sunny, he went out. There was never any need to count.

Still, I thought it odd that numbers larger than five did not crop up at all in Amazonian daily life. What if you ask a Munduruku with six children how many kids they have? "He will say, 'I don't know,'" Pica said. "It is impossible to express."

Anyway, he added, the issue was a cultural one. It was not the case that the Munduruku counted his first child, his second, third, fourth and fifth, and then scratched his head because he could go no further. For the Munduruku, the whole idea of counting children is ludicrous. Why would a Munduruku adult want to count his children? They are looked after by all the adults in the community, Pika said, and no one is counting who belongs to whom.

The reason for researching the mathematical abilities of these people who count only on one hand is to discover the nature of our basic numerical intuitions. In one of his most fascinating experiments, Pica examined the Indians' spatial understanding of numbers. How did they visualise numbers when spread out on a line? In the modern world we do this all the time – on tape measures, rulers, graphs and houses along a street.

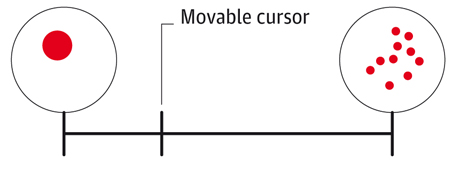

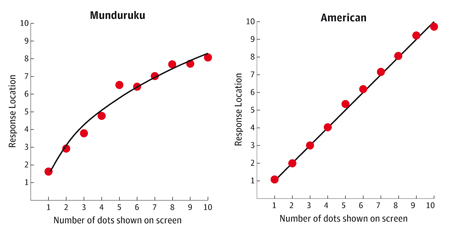

Pica tested them using sets of dots on a screen. Each volunteer was presented with a figure of an unmarked line. To the left side of the line was one dot; to the right, 10 dots. Each volunteer was then shown random sets of between one and 10 dots. For each set, the subject had to point at where on the line he or she thought the number of dots should be located. Pica moved the cursor to this point and clicked. Through repeated clicks, he could see exactly how the Munduruku spaced numbers between one and 10.

When American adults were given this test, they placed the numbers at equal intervals along the line. The Munduruku, however, responded quite differently. They thought that intervals between the numbers started large and became progressively smaller as the numbers increased. It is generally considered a self-evident truth that numbers are evenly spaced. It is the basis of all measurement and science. Yet the Munduruku visualise magnitudes in a completely different way.

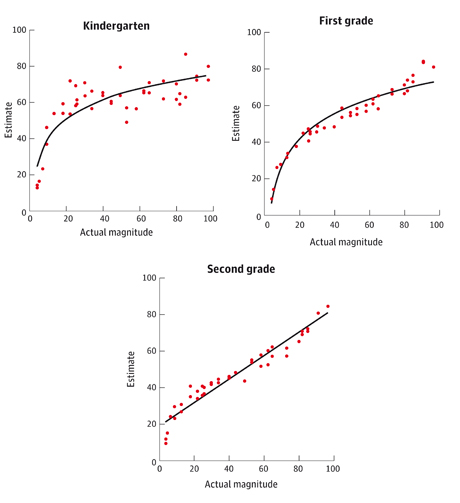

When numbers are spread out evenly on a ruler, the scale is called linear. When numbers get closer as they get larger, the scale is called logarithmic. And it turns out the logarithmic approach is not exclusive to Amazonian Indians – we are all born conceiving numbers this way. In 2004, Robert Siegler and Julie Booth at Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania presented a similar version of the number-line experiment to a group of kindergarten pupils (average age: 5.8 years), first-graders (6.9) and second-graders (7.8). The results showed in slow motion how familiarity with counting moulds our intuitions. The kindergarten pupil, with no formal maths education, maps out numbers logarithmically. By the first year at school, when the pupils are being introduced to number words and symbols, the curve is straightening. And by the second year at school, the numbers are at last evenly laid out along the line. There is a simple explanation. Imagine a Munduruku is presented with five dots. He will study it closely and see that five dots are five times bigger than one dot, but 10 dots are only twice as big as five dots. The Munduruku – and the children – seem to be making their decisions about where numbers lie based on estimating the ratios between amounts. When considering ratios, it is logical that the distance between five and one is much greater than the distance between 10 and five. And, if you judge amounts using ratios, you will always produce a logarithmic scale.

It is Pica's belief that understanding quantities in terms of estimating ratios is a universal human intuition, due to the fact that ratios are much more important for survival in the wild. Historically, faced with a group of adversaries, we needed to know instantly whether there were more of them than us. When we saw two trees, we needed to know instantly which had more fruit hanging from it. In neither case was it necessary to enumerate every enemy or every fruit individually. The crucial thing was to be able to make quick estimates of the relevant amounts and compare them; in other words to make approximations and judge their ratios.

The logarithmic scale also takes account of perspective. For example, if we see a tree 100 metres away and another 100 metres behind it, the second 100 metres looks shorter. To a Munduruku, the idea that every 100 metres represents an equal distance is a distortion of how he perceives the environment. Exact numbers provide us with a linear framework that contradicts our logarithmic intuition.

We live with both a linear and a logarithmic understanding of quantity. For example, our understanding of the passing of time tends to be logarithmic. We often feel that time passes faster the older we get. Yet it works in the other direction too: yesterday seems a lot longer than the whole of last week.

Our deep-seated logarithmic instinct surfaces most clearly when it comes to thinking about very large numbers. For example, we can all understand the difference between one and 10. It is unlikely we would confuse one pint of beer and 10 pints of beer. Yet what about the difference between a billion gallons of water and 10 billion gallons of water? Even though the difference is enormous, we tend to see both quantities as quite similar – very large amounts of water. Likewise, the terms millionaire and billionaire are thrown around almost as synonyms – as if there is not so much difference between being very rich and very, very rich.

Stanislas Dehaene is perhaps the leading figure in the cross-disciplinary field of numerical cognition. He started off as a mathematician, and is now a neuroscientist, a professor at the Collège de France and one of the directors of NeuroSpin, a state-of-the-art research institute near Paris. In 1997, he was having lunch in the canteen of Paris's Science Museum with the Harvard development psychologist, Elizabeth Spelke. They had sat down, by chance, next to Pierre Pica. Pica brought up his experiences with the Munduruku and, after excited discussions, the three decided to collaborate. The chance to study a community that doesn't have counting was a wonderful opportunity for new research.

Dehaene devised experiments for Pica to take to the Amazon, one of which was very simple: he wanted to know just what they understood by their number words. Back in the rainforest, Pica assembled a group of volunteers and showed them varying numbers of dots on a screen, asking them to say aloud the number of dots they saw. The Munduruku numbers are:

1 pug

2 xep xep

3 ebapug

4 ebadipdip

5 pug pogbi

When there was one dot on the screen, the Munduruku said "pug". When there were two, they said "xep xep". But beyond two, they were not precise. When three dots showed up, "ebapug" was said only about 80% of the time. The reaction to four dots was "ebadipdip" in only 70% of cases. When shown five dots, "pug pogbi" was managed only 28% per cent of the time, with "ebadipdip" given instead in 15% of answers. In other words, for three and above the Munduruku's number words were really just estimates. They were counting "one", "two", "three-ish", "four-ish", "five-ish". Pica started to wonder whether "pug pogbi", which literally means "handful", even really qualified as a number. Maybe they could not count up to five, but only to four-ish?

Pica also noticed an interesting linguistic feature of their number words. From one to four, the number of syllables of each word is equal to the number itself. This observation really excited him. "It is as if the syllables are an aural way of counting," he said. In the same way that the Romans counted I, II, III and IIII but switched to V at five, the Munduruku started with one syllable for one, added another for two, another for three, another for four – but did not use five syllables for five. When the number of syllables was no longer important, the word was maybe not a number word at all. "This is amazing, since it seems to corroborate the idea that humans possess a number system that can only track up to four exact objects at a time," Pica said.

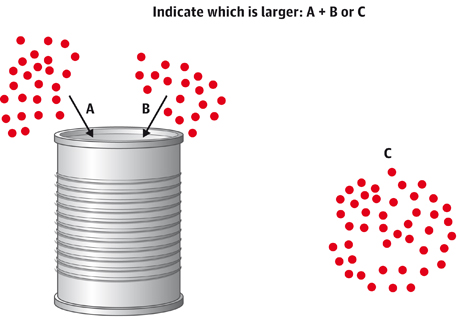

He also tested the Munduruku's abilities to estimate large numbers. In one test, the subjects were shown a computer animation of two sets of several dots falling into a can. They were then asked to say if these two sets added together in the can – no longer visible for comparison – amounted to more than a third set of dots that then appeared on the screen.

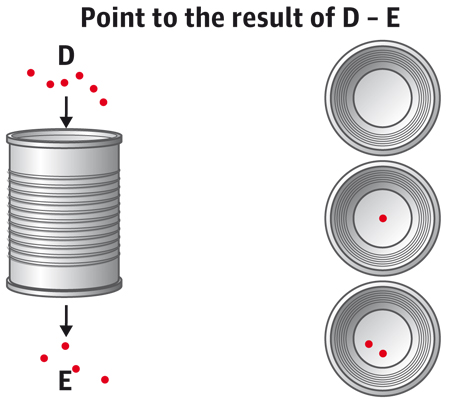

This tested whether they could calculate additions in an approximate way. They could, performing just as well as a group of French adults given the same task. In a related experiment, Pica's computer screen showed an animation of six dots falling into a can and then four dots falling out. The Munduruku were asked to point at one of three choices for how many dots were left in the can. In other words, what is six minus four? This test was designed to see if the Munduruku understood exact numbers for which they had no words.

They could not do the task. When shown the animation of a subtraction that contained either six, seven or eight dots, the solution always eluded them. "They could not calculate even in simple cases," said Pica.

The results of these dot experiments showed that the Munduruku were very proficient in dealing with rough amounts, but were abysmal in exact numbers above five. Pica was fascinated by the similarities this revealed between the Munduruku and westerners: both had a fully functioning, exact system for tracking small numbers and an approximate system for large numbers. The significant difference was that the Munduruku had failed to combine these two independent systems together to reach numbers beyond five. Pica said this must be because, for them, keeping the systems separate was more useful. And the fact that some Munduruku had learned to count in Portuguese but still failed to grasp basic arithmetic, was an indication of just how powerful their own mathematical system was and how well suited it was to their needs.

Could it be that humans need words for numbers above four in order to have an exact understanding of them? Professor Brian Butterworth, of University College London, believes that we don't. He thinks that the brain contains a ready-built capacity to understand exact numbers, which he calls the "exact number module".

According to his interpretation, humans understand the exact number of items in small collections, and by adding to these collections one by one we can learn to understand how bigger numbers behave. He has been conducting research in the only place outside the Amazon where there are indigenous groups with almost no number words: the Australian outback.

The Warlpiri Aboriginal community lives near Alice Springs and has words only for one, two and many. The Anindilyakwa of Groote Eylande in the Gulf of Carpentaria have words only for one, two, three (which sometimes means four) and many.

In one experiment with children of both groups, a block of wood was tapped with a stick up to seven times and counters were placed on a mat. Sometimes the number of taps matched the number of counters, sometimes not. The children were perfectly able to say when the numbers matched and when they didn't. Butterworth argued that to get the answer right, the children were producing a mental representation of exact number that was abstract enough to represent both auditory and visual enumeration. These children had no words for the numbers four, five, six and seven, yet were perfectly able to hold those amounts in their heads. Words were useful to understand exactness, Butterworth concluded, but not necessary.

Another important focus of Butterworth's work – and of Dehaene's – is a condition called dyscalculia, or "number blindness". It occurs in an estimated 3-6% of the population. Dyscalculics do not "get" numbers the way most people do.

For example, which of these two figures is biggest? 65 or 24? Almost all of us will get the correct answer in less than half a second. If you have dyscalculia, however, it can take up to three seconds. The nature of the condition varies from person to person, but those diagnosed with it often have problems in correlating the symbol for a number, say 5, with the number of objects the symbol represents. They also find it hard to count. Sufferers tend to rely on alternative strategies to cope with numbers in everyday life; for instance by using their fingers more. Severe dyscalculics can barely read the time.

Understanding dyscalculia has a social urgency, since adults with low numeracy are much more likely to be unemployed or depressed than their peers. Much of the research is behavioural, such as the screening of tens of thousands of schoolchildren in which they must say which of two numbers is the biggest. Some is neurological, in which magnetic resonance scans of dyscalculic and non-dyscalculic brains are studied to see how their circuitry differs. Gradually, a clearer picture is emerging of what dyscalculia is – and of how the number sense works in the brain.

Neuroscience, in fact, is providing some of the most exciting new discoveries in the field of numerical cognition. It is now possible to see what happens to individual neurons in a monkey's brain when that monkey thinks of a precise number of dots.

Andreas Nieder, at the University of Tübingen in southern Germany, trained rhesus macaques to think of a number. He did this by showing them one set of dots on a computer, then, after a one-second interval, showing another set of dots. The monkeys were taught that if the second set was equal to the first set, pressing a lever would earn them a reward of a sip of apple juice. If the second set was not equal to the first, then there was no apple juice.

After about a year, the monkeys learned to press the lever only when the number of dots on the first and second screens was equal. Nieder and his colleagues reasoned that during the one-second interval between screens, the monkeys were thinking about the number of dots they had just seen.

Nieder decided he wanted to see what was happening in the monkeys' brains when they were holding the number in their heads. So, he inserted an electrode two microns in diameter through a hole in their skulls and into the neural tissue. (At that size, an electrode is tiny enough, apparently, to slide through the brain without causing damage or pain.)

When the monkeys thought of numbers, Nieder saw that certain neurons became very active. On closer analysis, he made a fascinating discovery: the number-sensitive neurons reacted with varying charges depending on the number that the monkey was thinking of at the time. Furthermore, when a monkey was thinking "four", the neurons that preferred four were the most active, of course – but the neurons that preferred three and the neurons that preferred five were also active, though less so, because its brain was also thinking of the numbers surrounding four. "It is a noisy sense of number," explained Nieder. "The monkeys can only represent cardinalities in an approximate way."

It is almost certain that the same thing happens in human brains. Which raises an interesting question: if our brains can represent numbers only approximately, then how were we able to "invent" numbers in the first place?

"The 'exact number sense' is a [uniquely] human property that probably stems from our ability to represent number very precisely with symbols," concluded Nieder. Which reinforces the point that numbers are a cultural artefact, a man-made construct, rather than something we acquire innately.